温莎日记 70

A decomposition of growth in self-employment:CPB Netherlands Bureau for Economic Policy Analysis, Social Security UnitI.

A decomposition of growth in self-employment:

CPB Netherlands Bureau for Economic Policy Analysis, Social Security Unit

I. Introduction

The observed rise in self-employment in European region has amongst others been attributed to employment shifts amongst industries, changes in person organization, stimulating government policies and changes in person characteristics and preferences. In the Netherlands, the share of self-employed in the labour force during 1992–2006 has risen from 10.3% to 15.1% for men and from 6.0% to 8.5% for women. In this article, we disentangle this growth with particular focus on

- (i) sector composition effects and

- (ii) individual and household composition effects.

Comparable decompositions have been made for countries such as the United States and Canada. Fairlie and Meyer (2000) decompose the development of the US self-employment rate in multiple dimensions, including the age and industry composition. According to their findings, demographic developments, in particular ageing, could not explain much of the observed developments. In contrast, the shift of labour from industries with a low self-employment rate towards industries with a high self-employment rate could explain the most recent upturn in the self-employment rate. In addition, they find that the within-industry self-employment rate decreased strongly until 1970, and stayed flat from that year on.

Industries where self-employment occurs relatively often are agriculture, sales, hotels, repairs, craft and managerial or skilled occupations. Changes in industrial organization could influence self-employment as well. The institutional context may have an important effect on the prevalence of self-employment (Torrini, 2005), and institutional reform may therefore lead to growth. The OECD (2000) observes many efforts of national governments to foster self-employment.

Duggan (1998) shows that self-employment increased together with the intensity of policy measures aimed at this access. On the contrary, strict labour market regulations and policies may induce both employers and employees to circumvent these restrictions through self-employment. This raises the issue of 'false' self-employment, consisting of people who have no employees themselves and behave like employees–one principal, work that can also be done by a 'normal' employee, not as much responsibility as a 'normal' self-employed. The empirical literature has identified several institutional causes of such 'false self-employment'. A tax system favouring self-employment above regularization of employment may lead to tax evasion (Schuetze, 2000; Torrini,2005). Strong unions driving up wage rates may also lead employers to favour self-employed sub-contractors above regular employees (Collins, 1990). Finally, minimum wages drive out regular jobs for people whose productivity is lower than this minimum. The only alternative to find their way in the labour market is self-employment. The minimum wage effect on self-employment is, however, small in magnitude (Kamhi and Leung, 2005).

The choice for self-employment may be related to individual characteristics such as age, gender and health, and therefore demographic shifts may impact the overall self-employment rate. Using Austrian data, Leoni and Falk (2010) find that the difference between men and women is for an important part related to the field of study. In addition, the possibilities of flexible working hours and holidays are often seen as attractive features of self-employment, particularly by women who combine their work with the care for children (Edwards and Field-Hendry, 2002; Wellington, 2006). Finally, social norms may affect individual preferences. The rise of self-employment in the United Kingdom occurred simultaneously with an improved reputation of the self-employed (Meagre, 1994; Duggan, 1998).

II. Estimation

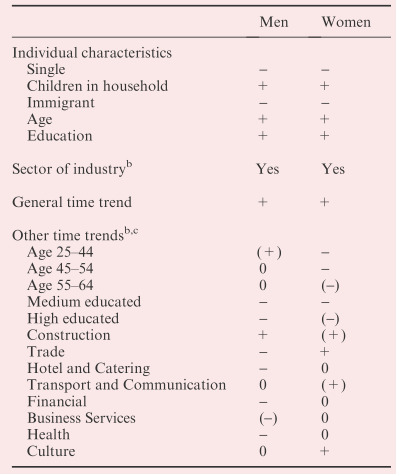

We employ a Logit model, where the probability of being self-employed is specified as a function of personal characteristics, industry and year of observation. In addition, we include interaction terms to control for several trends. Apart from the general time trend, all year dummies are interacted with industry, age and education dummies. Through this very flexible approach, we are able to unveil non linearities in the time trends of industry, age and education. We estimate the model for both men and women.

The probability to be self-employed increases significantly with age for both sexes. Men between the ages of 55 and 64 have a 42.3 percentage point higher probability to be self-employed than men between the ages of 15 and 24, whereas this difference is 40.9 for women. The age coefficients increase steadily with age. Higher education implies a higher probability to be self-employed, which points at a larger role of pull-factors than push-factors in the choice for self-employment. Finally, the industry the individual works in has a large effect on the probability to be self-employed. For both men and women, Hotel and Catering is the industry with the highest probability to be self-employed followed by Business Services, Trade and Culture.

The general time trend of the self-employment rate is clearly positive. This trend is especially strong during the last 3 years of our sample (2004–2006). The general time trend appears to be stronger for men than for women. The coefficients of the education interactions are in most cases significant and negative. This means that controlling for a general time trend, medium- and highly educated individuals are increasingly less likely to become self-employed. We observe a negative trend for women between the ages of 25 and 54. The self-employment propensity per age remains more or less constant for men. It is striking that the intra-industry development of self-employment is positive for women, whereas it is negative for men.

III. Decomposition

Using the results of the Logit estimations, we are able to make a decomposition of the development of the self-employment rate in the period 1992 to 2006 for both men and women. The contribution C of a group of variables X is calculated using the equation

where

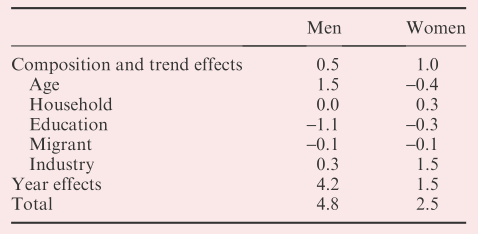

The decomposition shows that results are rather different for men and women. First of all, the industrial structure of the economy plays a limited role in explaining total growth for men, whereas it is much more important for women. For men, the industry dummies and interaction variables only explain 0.3 percentage points of the total upturn of 4.8%, whereas for women the variables explain 1.5 percentage points on a total of 2.5%. For men, the industry effect is nearly a pure composition effect, whereas this hardly affected the self-employment rate of women. For women the most important sectoral shifts were seen in the Manufacturing, Health and Trade sectors, and the self-employment rates in these sectors are practically in line with the aggregate self-employment rates for female-labor participation.

Compared with the industrial structure, the ageing of the labour force explains much more of the upturn of self-employment for men than for women. For men, the higher share of older workers increases the aggregate self-employment rate by 1.5 percentage points, whereas it decreases the rate for women by 0.4 percentage points. The lower effect for women is mainly caused by the interaction variables of the age groups with the time trend. Older women initially do have a higher propensity to be self-employed than younger women, but the difference with younger generations of women has become smaller and smaller over time.

The year dummies have a very large impact on the self-employment rate. For men, a large part of the 4.8 percentage point increase since 1992 can be related to year effects and for women more than half of the 2.5 percentage point increase. These large year effects imply that most of the observed growth cannot be explained by changes in sector composition and individual and household characteristics. Unobserved individual characteristics and cultural developments could play a role, but given the large year effects in the final years of our sample (2004–2006) it is likely that government policies have played a more significant role in the upturn of self-employment. However, we are not able to identify these effects with our dataset.

IV. Conclusion

The latter could be related to the improved reputation of self-employed. During the period 2000 to 2006a series of policy measures were taken, and the strongest effects are seen precisely during these years. The results show that differences between men and women are substantial. For men, we find that the ageing of society is an important cause of the observed increase, which is however largely undone by higher education level of younger generations. Medium- and highly educated men are increasingly less likely to be self-employed compared with low-educated men. The industrial composition only plays a small role in explaining the upturn. For women, we find that intra-sectoral developments have been important in spurring self-employment whereas sectoral shifts only play a limited role. The 'unexplained part' is large for both men (89%) and women (62%). This can be interpreted as a 'generic time trend'.

V. Code 5102

x=xlsread('C:UsersShihaoDesktopEC5102EC5102 PS4Q1.xlsx'); GDP=x(1:248,1);nnhpGDP_wolg=hpfilter(GDP,1600);nplot(GDP)nhold on hpGDP_wolg=hpfilter(GDP,1600);nplot(hpGDP_wolg) hold offnconsumption=x(1:248,2);nhpconsumption_wolg=hpfilter(consumption,1600);ninvestment=x(1:248,3);nhpinvestment_wolg=hpfilter(investment,1600);nlgGDP=log(GDP);nlgconsumption=log(consumption);nlginvestment=log(investment);n[hpGDP,c_hpGDP]=hpfilter(lgGDP,1600);n[hpconsumption,c_hpconsumption]=hpfilter(lgconsumption,1600);n[hpinvestment,c_hpinvestment]=hpfilter(lginvestment,1600);navggdp=mean(GDP);navgconsumption=mean(consumption);navginvestment=mean(investment);navghpgdp=mean(hpGDP);navghpconsumption=mean(hpconsumption);navghpinvestment=mean(hpinvestment);nsharec=mean(consumption)/mean(GDP);nsharei=mean(investment)/mean(GDP);nstdc_hpGDP=std(c_hpGDP);nstdc_hpconsumption=std(c_hpconsumption);nstdc_hpinvestment=std(c_hpinvestment);nratiocongdp=stdc_hpconsumption/stdc_hpGDP;nratioinvestgdp=stdc_hpinvestment/stdc_hpGDP;ncorrcongdp=corr(c_hpconsumption,c_hpGDP);ncorrinvestgdp=corr(c_hpinvestment,c_hpGDP);nGDPt0=c_hpGDP(1:247,1);nGDPt1=c_hpGDP(2:248,1);nconsumptiont0=c_hpconsumption(1:247,1);nconsumptiont1=c_hpconsumption(2:248,1);ninvestmentt0=c_hpinvestment(1:247,1);ninvestmentt1=c_hpinvestment(2:248,1);ncorrgdpt1t0=corr(GDPt1,GDPt0);ncorrcont1t0=corr(consumptiont1,consumptiont0);ncorrinvestt1t0=corr(investmentt1,investmentt0);

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Andre van Stel, Robin Douhan, Nicole Bosch and Mark Roscam Abbing for their valuable comments on earlier versions of this article.